Where are future generations in newspaper coverage of climate change?

by Hilary Graham and Siân de Bell · Published · Updated

Climate change is accelerating – and will impact most on children and those yet to be born. The failure to halt the relentless rise in global temperatures is an act of intergenerational injustice in which the UK is centrally implicated. It is among the top national contributors to global fossil fuel emissions and, as the first industrialising country, has made the largest per person contribution to climate change.

Climate change is accelerating – and will impact most on children and those yet to be born. The failure to halt the relentless rise in global temperatures is an act of intergenerational injustice in which the UK is centrally implicated. It is among the top national contributors to global fossil fuel emissions and, as the first industrialising country, has made the largest per person contribution to climate change.

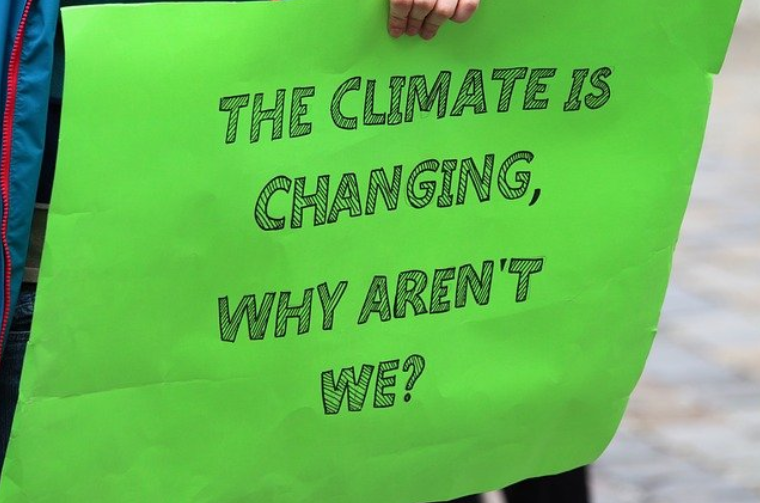

While today’s children and tomorrow’s generations will be hardest hit, they have no direct voice in society. It is adults who vote in elections, decide on policies and run the country. Shaping adult views is the media, a dynamic system of traditional and digital technologies. National newspapers are pivotal to this system. They gather information and then selectively repackage and distribute it across multi-media platforms, including social media. Most climate change tweets on Twitter are linked to coverage by newspapers and public broadcasting corporations.

Our study explores whether and how future generations – children and those born in the future – are represented in climate change coverage in UK newspapers. We selected four newspapers, each with an audience of over 10 million. The Mirror and the Mail focus predominantly on domestic and celebrity news while the Guardian and Telegraph provide greater coverage of national and international events. The Mail and Telegraph are politically right-leaning while the Mirror and Guardian are left-leaning.

We examined climate change coverage from 2010 to March 2019, a period that included the signing of the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit climate change and the first global school strikes in March 2019. Using an online newspaper database to identify articles covering climate change, we found only a minority – less than one in ten – refer to future generations. Where they are mentioned, it is almost always in single-statement references tangential to the main story. In articles full of facts and figures, they give climate change a human face and provide a moral case for action.

For example, a 400-word article in the Mirror reported on the rapid rise in global temperatures without mentioning future generations, bar a statement towards the end from a leading scientist: ‘we have the knowledge and the tools to act. We have a choice. Future generations will not.’ Similarly, a long article in the Telegraph describing how ‘global warming continues to pick up pace’ included a short quote from the head of a climate research organisation: ‘we need to act now, otherwise we will jeopardise the future of our children, grandchildren and many generations.’

Who speaks for future generations?

As in other domains of society, future generations are represented by adults. In the articles that referred to them, only 2% include the views of young people themselves. Only one article – published at the time of the global school strike – was authored by young people (by Greta Thunberg and colleagues).

The spokespeople are adults already in the public eye: those leading climate change events and scientific reports or, more typically, government leaders and other public figures, including Mark Zuckerberg, Stephen Hawkins and Leonardo Di Caprio. An example is given here:

Prince Charles has blamed the catastrophic flooding in Cumbria on a global refusal to combat the ‘root cause’ of climate change. In a speech to a gathering of global finance chiefs, he attacked ‘climate change sceptics’ for ignoring an ‘accelerating economic, social and environmental disaster’, of which the current flooding in the north of England, he claimed, was simply one example….’What right do they have to sacrifice our children and grandchildren’s future?‘ (Dec 2015; Mail, article length: 609 words).

Who are future generations?

Many articles use broad references like ‘generations to come’ ‘coming generations’ ‘generations yet to be born’. Others include terms that give future generations a clearer temporal location (‘children’, ‘today’s children’, ‘the next generation’) and relational identity (‘our’ and ‘your’ children and grandchildren). But, even when such framing is used, climate change is very rarely described in generational time. Thus articles refer to the need to ‘find a common solution that will secure a future for generations to come’ (Telegraph) and ‘protect the world we leave to our children’ (Mail), without giving an indication of either the timescales to achieve these goals or the types of action required.

Only a handful of articles translate facts about climate change into personal and generational times. As a rare example, a scientist noted that ‘keeping global warming below 2°C basically means ending fossil fuel use well before today’s children start drawing their pensions’ (Telegraph). The article by Greta Thunberg and colleagues puts it more bluntly: ‘those who are under 20 now could be around to see 2080, and face the prospect of a world that has warmed by up to 4C. The effects would be utterly devastating’ (Guardian). We found no articles discussing broader social inequalities: for example, how climate change is disproportionately affecting the poorer global south in which most of today’s children live.

Changing the public conversation on climate change

We found that future generations are marginal to UK press coverage of climate change. Where they feature, it is via celebrity ‘soundbites’ on the moral imperative of taking action – but within articles that give them no voice.

Like the youth climate change movement, the UK press has global reach – and can help to shift the public conversation about climate change. For example, newspapers could enable young people to be their own spokespeople and could represent climate change in terms of people’s lifetimes. For example, ‘by the end of the century’ becomes ‘within the lifetime of a child born today’ and ‘by 2030’ becomes ‘before Britain’s 6 year-olds are able to leave school’. Working with civil society – local groups, faith communities, national charities and UN agencies – they could support young people in protecting the planet for future generations.

About the Authors.

Hilary Graham is a sociologist who specialises in public health and climate change. Since 2005, she has been Professor of Health Sciences at the University of York. Hilary is part of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, coordinating the Countdown group tracking public and political engagement in health and climate change. She is also an Associate Director of the new ESRC Centre for Climate and Social Transformations (CAST) led by the University of Cardiff

Dr Siân de Bell is an Impact Fellow at the European Centre for Environment and Human Health (ECEHH), University of Exeter, working with stakeholders in the southwest to support investment in the environment for health and wellbeing. She was awarded her PhD in Health and Environment by the University of York in 2018, for her research relating to the integration of ecosystem health and human health.

1467-7660/asset/DECH_right.gif?v=1&s=a8dee74c7ae152de95ab4f33ecaa1a00526b2bd2)

1756-2589/asset/NCFR_RGB_small_file.jpg?v=1&s=0570a4c814cd63cfaec3c1e57a93f3eed5886c15)