The Psychiatrization of Society: Why we should care

by Timo Beeker ·

Some years ago, I started my residency as a psychiatrist in a hospital close to Berlin. I was prepared for my job also to encompass meeting people who were not very pleased about meeting me. As one of the downsides of my career choice, I expected to inevitably become a part of the disciplinary institution that Foucault and others had famously described (Foucault 1965; Goffman 1961; Szasz 1974), being obliged to play a main role in cases of compulsory treatment and involuntary hospitalizations, at least occasionally. Although these cases were rarer than I had anticipated, they existed and were undoubtedly the worst part of the job profile. So far, my expectations had proved right.

Some years ago, I started my residency as a psychiatrist in a hospital close to Berlin. I was prepared for my job also to encompass meeting people who were not very pleased about meeting me. As one of the downsides of my career choice, I expected to inevitably become a part of the disciplinary institution that Foucault and others had famously described (Foucault 1965; Goffman 1961; Szasz 1974), being obliged to play a main role in cases of compulsory treatment and involuntary hospitalizations, at least occasionally. Although these cases were rarer than I had anticipated, they existed and were undoubtedly the worst part of the job profile. So far, my expectations had proved right.

What I had not seen coming about being a clinical psychiatrist, is how much effort I had to dedicate to patients who did not want to leave the psychiatric ward after weeks or months of in-treatment and despite being reasonably well again. Even more surprisingly, when working shifts at the emergency department, I realized that I spent an incredible amount of my time negotiating with people who explicitly wished for psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, and sometimes hospitalization, although a clear medical reason was lacking. Quantitatively speaking, being a psychiatrist nowadays appeared to me to consist much more in keeping people out of the disciplinary institution than keeping people in. And as much as I still feel repulsed by the “keeping-in” part of my job, I was and still am irritated by the other part.

Conversations with colleagues confirmed that I was not the only one experiencing this seemingly paradoxical shift in the role of clinical psychiatrists. Older colleagues sometimes hinted that the pressures on psychiatry had steadily increased since they had been residents. Far from lamenting that everything used to be better in the old days, it seems safe to say that something has changed about psychiatry and its role in society: For example, there is solid evidence that psychiatric in- and outpatient services are increasingly requested (Olfson et al. 2019; Lipson et al. 2019), correlating with a constant growth of treatment capacities (hospital-beds, day-clinics, home-treatment-teams, ambulatory care etc.) and a surge in per capita consumption of psychotropic medication (Thom et al. 2019,OECD 2015). Meanwhile, judging from the inflationary use of terms like ‘paranoid’, ‘autistic’ or ‘traumatized’ in our everyday language, from popular TV-series with mentally ill protagonists, or the myriads of articles speculating which psychiatric diagnosis would best describe Donald Trump (Lee 2017; Hughes 2019), psychiatric concepts have apparently snuck into wide parts of culture and society.

How can we make sense of this all? How do the irritations in psychiatric every-day business fit to the macro-level developments of psychiatric healthcare and to the broader changes in attitudes towards psychiatry in society? One interpretation could be to understand all these points as being sub-processes of a larger process, which is the progressing psychiatrization of society. In short, psychiatrization could be conceptualized as a specific – and nowadays perhaps the most influential – type of medicalization, consisting in a complex process of interaction between individuals, society and psychiatry, through which psychiatric institutions, knowledge, and practices affect an increasing number of people, shape more and more areas of life, and further psychiatry’s importance in society as a whole (Beeker et al. 2021a). This expansion may be facilitated by a broad variety of drivers, among them changes in classificatory systems that turn a growing number of people into psychiatric patients (Frances 2013, Paris 2015), the steady growth of the psychiatric healthcare system, or the countless mental health apps through which psy-knowledge also creeps into the private lives of people who would normally not consider seeking advice from a psychiatrist for their problems (Kumar 2017, Beeker & Thoma 2019; Cosgrove et al. 2020).

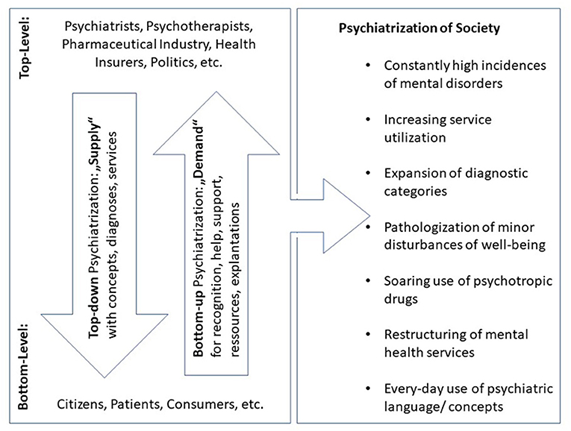

How does psychiatrization work? Criticisms of psychiatric expansion have traditionally focused on the most obvious culprits (Illich 1975; Healy 2012; Whitaker & Cosgrove 2015). While it is undisputable that psychiatric corporate interest or the pharmaceutical industry are playing main roles in the ongoing lowering of thresholds for diagnosis and treatment, too narrow a focus on them risks being reductive. Also, it implies that people who become psychiatric patients are merely passive objects of psychiatrization. But the agency and activity of laypeople without professional ties to the healthcare-system should by no means be underestimated: The history of the inclusion of PTBS into the DSM (Scott 1990), the branding of ADHD as ‘neurobiological life-span disorder’ (Conrad & Potter 2000), ongoing debates about the incorporation of various psychosomatic syndromes into psychiatric nosology (Barker 2002), or the growing influence of patient-advocacy-groups are good examples for the power of bottom-up-psychiatrization (Hande et al. 2016). And, last but not least, there are many people who actively consult professionals wishing for psychiatric ‘help’ for relatively minor complaints – and who will rarely be disappointed. Further inquiry into psychiatrization should, thus, aim at grappling with both top-level and bottom-level agents and the dynamics between these two poles (see, figure 1). These might largely resemble a dynamic of supply and demand, in which the supply (psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, resources) may induce the demand – and vice versa!

Top-down and bottom-up psychiatrization. Main protagonists and vectors of psychiatrization consisting of heterogeneous sub-processes, of which the most important are listed on the right side of the figure. First published in: Beeker et al. 2021a.

Why should we care? Just like medicalization, psychiatrization has ambivalent effects. For instance, the dissemination of psychiatric infrastructures can lead to better availability of services in underserved regions. However, there is a variety of serious risks: Individuals may be subjected to overdiagnosis and overtreatment, including short and long-term side-effects of medication (Whitaker 2010), but also through psychiatric diagnosis, which may turn into self-fulfilling prophecies by reinforcing (self-)stigma and diminishing self-efficacy (Livingston & Boyd 2010). Psychiatrization may also promote widespread ‘inverse care’, when psychiatric services are tailored to the needs of the more frequent and thus more profitable ‘worried well’, instead of providing help for those who need it most (Hart 1971). From a societal perspective, psychiatrization may further narrow down the range of ‘normalcy’ and intensify neoliberal imperatives of performance and functioning. And finally, when it comes to essentially social and political problems such as poverty and its effects, psychiatrization risks inciting short-time medical troubleshooting while hindering long-term political problem solving (Davies 2017; Klein & Mills 2017).

What can we do? Critics of the psychiatric healthcare-system and its ideological underpinnings have suggested several measures which aim at countering primarily overdiagnosis and overtreatment, among which are introducing stepped diagnosis (Batstra & Frances 2012), limiting the influence of pharmaceutical companies and psychiatric corporate interest (Frances 2013; Whitaker & Cosgrove 2015) or fostering user-involvement in care and research (Gillard et al. 2010; Wright & Kongats 2018; Beeker et al. 2021b). From a scientific point of view, the top-priority would rather be to collect more empirical evidence about the scope and the various impacts of psychiatrization as well as to clarify its drivers and mechanisms. However, whether operating from the practical or the scientific angle, it seems important to keep in mind that psychiatrization cannot be reduced to being exclusively a problem of psychiatry as an isolated medical specialty. The engagement with psychiatrization requires a much broader perspective that will lead to such fundamental questions as who we are and how we want to live individually and as a society.

Full article: Beeker T, Mills C, Bhugra D, te Meerman S, Thoma S, Heinze M and von Peter S (2021) Psychiatrization of Society: A Conceptual Framework and Call for Transdisciplinary Research. Front. Psychiatry 12:645556. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.645556

1754-9469/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=9197a1a6ba8c381665ecbf311eae8aca348fe8aa)